The scientific peer review process benefits greatly when the study section reviewers bring not only strong scientific qualifications and expertise, but also a broad range of backgrounds and varying scientific perspectives. Bringing new viewpoints into the process replenishes and refreshes the study section, enhancing the quality of its output.

In this context, CSR recently removed the requirement to have at least 50% full professors on committees. This had sometimes led to a misguided attempt to “do better than the metric” by aiming for a committee of all full professors. We are now encouraging scientific review officers (SROs) to focus on scientific contributions (demonstrable in a range of ways, e.g. recent publications, R01 or equivalent extramural funding from other sources, etc.), expertise, and breadth instead of trying to meet a career-stage metric. Our goal is to achieve a balance of perspectives by including a mix of qualified senior, mid-career, and junior scientists on study sections.

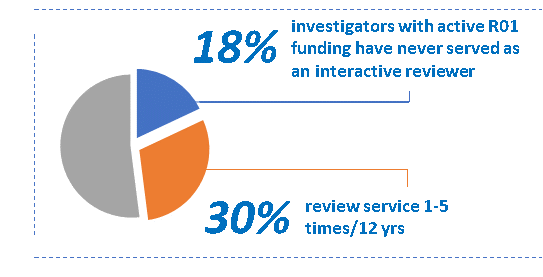

In an effort to facilitate broader participation in review, we are making these data available to SROs and encouraging them to identify qualified and scientifically appropriate reviewers, who may not have been on their radar previously. In another step to broaden the pool of reviewers, we will launch a web page this spring through which scientific societies can recommend qualified reviewers.

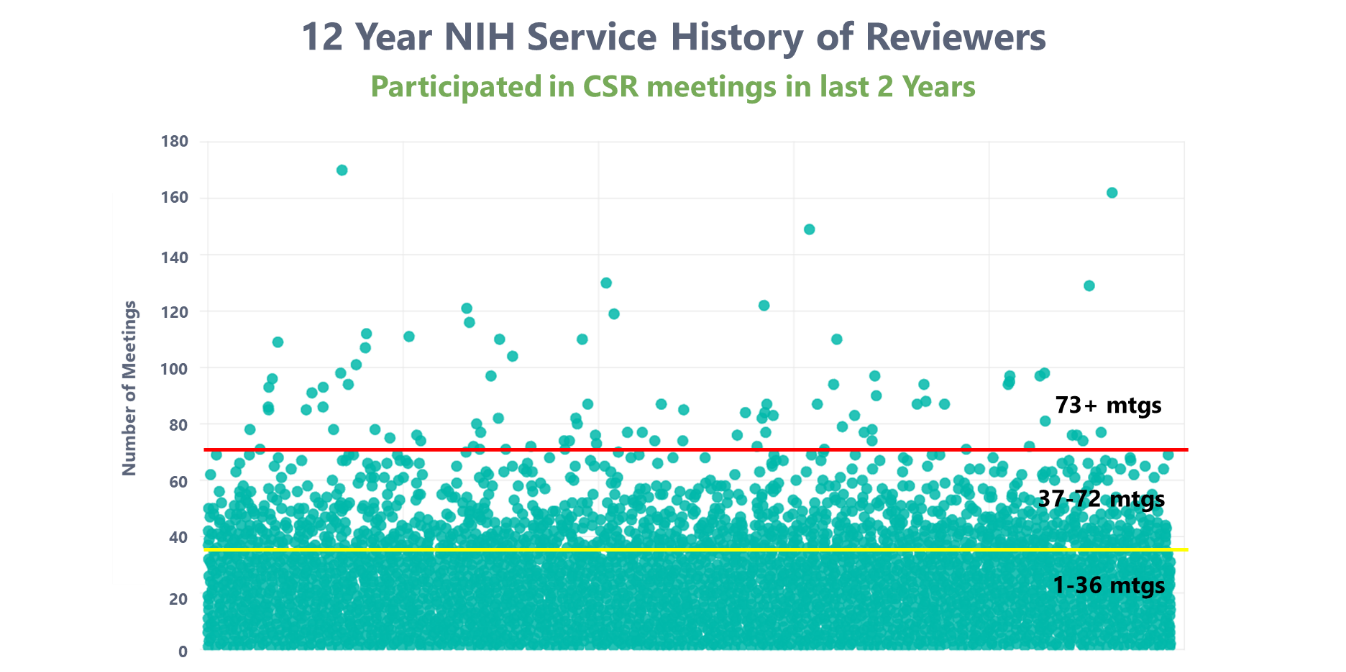

We greatly appreciate the generosity of reviewers who contribute to the scientific community by freely giving their time to review NIH grant applications. However, one aspect of broadening the pool of reviewers is to avoid excessive review service by a small fraction of people, which can lead them to have a disproportionate effect on review outcomes. We are looking into issue of undue influence, or the “gatekeeper” phenomenon, where a reviewer has participated in the NIH peer review process at a rate much higher than their peers, and thus has had a disproportionate effect on review outcomes in a given field. Below is a plot examining the service records of all 24,642 reviewers who served as reviewers (in a capacity other than as a mail reviewer) for CSR within the past two years. Each dot represents a reviewer’s number of meetings for the NIH over the last 12 years.

Below the yellow line are reviewers who have served one to 36 times in 12 years—these make up 94% of the total pool and include the vast majority of the reviewers used. Between the yellow and red lines are reviewers who have served at 37 to 72 meetings over 12 years, 5% of the pool. The small number of reviewers above the red line have served at 73 or more meetings in 12 years; this is the sort of excessive review service that raises concerns about undue influence.

To actively manage undue influence, we have asked SROs to check review service records prior to inviting reviewers. In addition, based on our analysis of the reviewer service data and the unanimous recommendation of the CSR Advisory Council, we are discontinuing (NOT-OD-20-060) the “recent substantial service” policy that extended continuous submission benefits to those who served 6 times over a period of 18 months (6 times in 5 rounds). This policy, established in 2009 with the best of intentions to incentivize review, has led to the unintended consequence of encouraging excessive ad hoc review service within a short time frame. Implementation of this change will be gradual, maintaining eligibility for those reviewers who have already served, and honoring commitments to those who are serving now and will continue to serve through June 30, 2020, the end of the current eligibility period. Continuous submission eligibility for appointed members of NIH study sections and committees will not change. Policies surrounding late submission of applications also are unaffected (NOT-OD-15-039).

CSR’s mission is to provide a fair, independent, expert, timely review – free of inappropriate influences – so the NIH can fund the most promising research. CSR continues to work to broaden its scientific review groups because a diversity of expert perspectives better allows identification of potentially high-impact research, which benefits all of us.

If you haven’t served recently, we hope you will do so if asked.

I am in the top 2-3% of he graph. One reason that some of us have served on many study sections is because we are well-trained and perform excellent reviews (which is why SROs invite us back to review). Yet, I still appreciate the need to broaden the pool of reviewers. I would like to ask how the new reviewers will be trained. The instructions from NIH re a good start, but a good reviewer has a feeling for the process that extends beyond the ‘rulebook’, similar to how a basketball player understands basketball beyond just the rulebook. A broader pool of newer, inexperienced, untrained reviewers does nto sound better than a more narrow pool of expert reviewers, so some thought is needed about how to train new reviewers. Just because a researcher has a R01 grant does not mean that the researcher truly understands how to review grants. I would look forward to the opportunity to forego being a grant reviewer in the future, in exchange for the opportunity to help train new reviewers.

We invest a lot of effort in training reviewers. Scientific Review Officers (SRO) train reviewers every round, for every meeting they run. Standing panels always have ‘early career reviewers’ and usually there are also ad-hoc reviewers who are either new to review or new to the particular SRO. SROs run pre-meeting teleconferences with their reviewers every meeting – often SROs break it up into one training session for experienced people that is focused on recent changes in review or particular things the panel needs to work on and a second training session for those new to review. The reviewer guides for grant mechanisms, criteria spelled out in FOAs, and policies on evaluating rigor and reproducibility form the basis for this training. We are currently developing online training modules for reviewers. (Our first effort was recently finished and is focused on review integrity.) Developing online modules will not only allow for more consistency in training across CSR, we can share these modules on our web site with everyone. PIs will be able to see exactly how we train reviewers evaluating their proposals. We agree – there is a difference between knowing the rules and applying them well. The pre-meeting training is just a small part of what we do. SROs read preliminary critiques in advance of the meeting and spend a great deal of time interacting with new reviewers to make sure that their critiques are clear, substantive, appropriately apply the review criteria, and that comments fit the numerical scores.

This comment overlooks two key points. First, “well trained” sounds fine and all, but adequate grant review talent is not the province of only the elite few. There are plenty of people who do a fine job and plenty who would do a fine job if given a chance. Most people who report on their first study section experience are semi-awed that despite their uncertainty, their very first scores were very similar to those of the experienced members of the panel. Hey, maybe CSR could crunch some numbers and finally put to rest this old chestnut that somehow every new reviewer blows up everything with their incompetence. It’s just not so, in my reviewing experience.

Second point: grant review is an inherently subjective process wherein the biases and preferences of the reviewers dictates what scores well. The NIH system’s successes stem from its very diversity of letting a broad range of subjects gain access to research funding. As the blog entry puts it “a broad range of backgrounds and varying scientific perspectives” is absolutely the goal here. Having primary peer review input from a select few fights against this. It’s counter to the NIH’s desire to fund the best science.

Please consider providing a living wage to compensate reviewers for their time, to encourage a more diverse pool. Reviewers often commit 40-60 hours of time for only a few hundred dollars of reimbursement. This most negatively impacts lower income scientists, which disproportionately consist of minorities and women. Although some universities will pay faculties’ salaries during the time they are on review panels, many faculty at smaller institutions count on summer teaching salaries to make ends meet, and so are not able to take time off to participate in review panels. In addition, reviewers for SBIR/STTR proposals are often from non-academic positions that will not compensate for their time. I would encourage CSR to do a more thorough analysis of PI’s who are eligible to serve on review panels; whether money is a factor in whether they accept the opportunity to participate on the panel; and the resulting makeup of the panels in terms of diversity.

Unbiased reviewing process is the key. Productivity is the key also. PI productivity should be weighed as important as the science itself part.

Great move. Publication and expertise should be the focus of choosing the reviewers. In fact, keeping the minimum 20% reviewers at the assistant professor level will create a good pool in the peer-review process. If I read comments on my application I can tell that comments were written without reading the proposal. At the same time, some reviewers are so great since they always provide constructive comments which allow applicants to improve their application. I feel there is no replacement for senior and experienced scientists. In my opinion, Keeping 40% professor, 35% associate professor and 25% assistant professor with a good track record of publication and grantsmanship will improve reveiw process.

The best thing to happen to the review process was when preliminary scores/reviews had to be posted before the study section convened. I saw SO MANY reviewers showing up without having read the proposals in any detail. This happened across my years of reviewing proposals. I disagree that it’s best to have a higher percentage of full professors. My institution didn’t have those ranks (scientist, senior scientist, instead), and I found some of the full professors to be closed to new ideas and new approaches. Too often, academics seem to see a positive review as potentially taking money out of their own coffers. It isn’t that adding junior people helps, but it does help to reach out to qualified persons beyond academia.

I don’t think people should go more than once per round and CSR should give other people opportunities.

While I realize that NIH is trying to improve the grant review system, appointing junior researchers to review grants is not going to help. I have served on many study sections, both as a permenant member and ad hoc, and the most seasoned senior faculty are the best and generally most understanding of junior researchers grants. I would support the idea of mandatory service on a review panel if NIH asks. The argument against this has always been…you’re just going to annoy people who have to serve and they won’t do a good job. Well, if everyone is annoyed then no one is really annoyed.

NIH should stay focused on the best quality of reviewers as possible. This will undoubtably be more seasoned and senior people. There is not substitute for experience in any endeavor including science. There is a hint of ageism in this new policy.

This is a valuable discussion, also as viewed from across the pond as someone who has carried out substantial reviews on both shores. Neither science or education is apolitical. Whether either should be is beside the point. They cannot be but a part of the complicated structures in which we live. The review of scientific proposals should involve, not only those who are experts in the field, but also those adjacent to their science as well as the community the science is intended to benefit. Interdisciplinarity and outreach is required throughout the scientific process, most especially when reviewing proposals for research and the findings of research. Without having to speak to the experiences and voices outside their immediacy, group think is threatened and the specific science discipline is likely to fold in on itself, stagnate and potentially lead to poor outcomes or even outcomes that are damaging to those for whom the science is intended to benefit. Ultimately the integrity of the research process relies on the confrontation with what is unexpected and challenging.

Director Byrnes’ review of the CSR’s mission should be welcomed. The eventual broadening of the NIH review groups should contribute to a better “identification of potentially high-impact research, which benefits all of us.” This is what we all should want.

As an investigator who has been “in the NIH system” as an applicant/awardee and as a reviewer for over 35 years, I appreciated all of the thoughtful comments of my colleagues who responded. I was especially impressed with the comments/ suggestions above from Bert Singlestone and Kenton Sanders, and some of my experiences match their cumulative experience. There are problems with having panels weighted too heavily in either direction regarding seniority, but it us very clear in the current system that negative comments/evaluations have much more impact than positive ones, and this will have the effect of reducing support for the most innovative science. I would like to see the NIH seriously consider revamping the system as suggested by Kenton, as it could produce better outcomes and save a lot of money; perhaps it could be tried on a smaller scale for certain classes of applications, eg., MIRA or R21.

Finally I am amazed that anyone is able to participate regularly in 3 different panels per cycle over a long period of time. When I’m serving on a regular RO1-based panel, I typically spend at least a couple of weeks worth of time preparing my reviews. For me, 9 panels/year would add up to 18 weeks spent on grant reviewing and I would never get any of my own funded work done. I guess I must read and write more slowly than these very active reviewers…

This policy is a step in the right direction for increasing access to NIH grant funding. The more experienced reviewers must make room for the younger and less experienced.

While nothing is ever perfect, this seems to be a move in the right direction. Those of us who have submitted grants and manuscripts and served as reviewers as well as having been on the receiving end know full well that reviewers’ comments can be enlightening and well placed but sometimes also miss the mark if you are assigned to a reviewer who does not understand what good peer review entails. Moreover we should applaud and appreciate those reviewers who have served frequently and whose experience likely contributed positively to the review process. However, it is also necessary to expand the pool of reviewers because it has been well documented that our scientific workforce does not show a healthy age distribution and if we want science to maintain a level of integrity in the future, younger scientists also need to be mentored so that they can become competent peer reviewers as the seasoned reviewers head for retirement. Perhaps scientists who are invited as reviewers could be vetted based on their history as fair and objective peer reviewers on manuscripts and that those with an unsavory track record of subjective caustic reviews might be passed over. Certainly, recipients of grant funding should recognize that they should return the privilege of being an award recipient by volunteering to serving as reviewers as they gain experience in navigating the process. This should be viewed as a responsibility to be taken seriously and treated respectfully in order to maintain the integrity of the scientific community at large.

Before anyone else suggests that everyone be asked to serve on study section at least once a year, I would ask you to walk around the room during a study section. How many participants are on their laptops during the discussion, answering emails, editing manuscripts, online searching, and paying what appears to be little attention to the discussion? How many members do not engage in any discussions outside their assigned grants? The number is already too high and would clearly go up further if everyone is asked to serve, some unwillingly.

I have chaired a few study sections and worked with different SROs and found them uniform in their outstanding diligence and attention to diversity in study section composition; geographic, gender, seniority, degree, research field, etc. But let’s be honest here, there are more than 18% of PIs who simply should not serve on study section unless they up their game, spend the time, become willing to read grants several times and critically to provide both study section members and the PI of the grants they review the informed and balanced review that are critical to the process.

I also echo the comment above. using the same reviewers again and again helps to form interest groups.

This is such excellent news. While I’m sure many senior folks with extensive service have only the best of intentions, I have witnessed a few senior individuals use their extensive connections to NIH to gate-keep, as well as keep on the pulse of science. Also, I suspect that the 18% of individuals whom have not served is largely because they have not been asked – not because they are not willing. And finally, as a mother, extensive time away from my family is difficult and 9+ meetings a year is something I will likely never be able to maintain. Seeing the service of my senior colleagues, I have worried how I could ever keep up. But I believe this policy will do a lot for leveling the scientific playing field for those of us with family obligations, as well. Excellent job NIH.

I agree wholeheartedly with these recommendations. I have seen frequently Professors on study sections who do not have active NIH support and their knowledge base is dated and are on the section for no other reason then their status as professors. They know the ropes and can be very persuasive in expressing their point of view.

I appreciate NIH’s efforts to spread the load – and the influence – of reviewing equitably across career stages and of course across gender/race/type of institution.

If you really want to broaden the review process, do not limit it only to reviewers who have had a previous RO1. That promotes intellectual incest. There is a research world outside of NIH and it is rather presumptuous to believe that only RO1 recipients are qualified to evaluate NIH grant proposals. I have had only one 3yr RO1 in 40 years, but >$12M in other research support in infectious disease epidemiology from other federal agencies and private foundations. I was asked to serve on a study section once early in my career, but was never invited again because I was too critical of the research being supported. I have also served on NSF panels which are much more rigorous (7 written reviews) and with much less money. The NIH review process needs more than broadening. It needs an over-hall.

Do the numbers in the article (such as those with active R01 funding who have never served) refer only to service on CSR study sections? The second figure explicitly states “Participated in CSR meetings …”. Many institutes have their own study sections. Although I have served 73+ times in the past 12 years, almost all of that has been for reviews managed by NHLBI and NIAMS rather than CSR.

A policy to consider changing is that while serving on an NIH advisory council one cannot review NIH grants — not even those submitted to a different institute. I can understand that it would not be appropriate to review grants submitted to the institute for which one is serving on the advisory council, but why not even for other institutes? As a biostatistician I work with investigators in several unrelated disease areas.

I serve NIH regularly because I do believe that NIH is one of the best agencies for good for humankind. Would be excellent to see a broader range of young scientists, including postdocs in sitting in review panels. I do take my hat off to the work of Program Officers and Scientific Review Officers. It is very complex and demanding. Would be great if we all together improve the system.

I echo the comment above. The NIH should require all PIs who receive NIH funding to serve at least one round per year. A small price to pay for research support.

I could not agree more. A commitment to serve at some minimal level (i.e. whether once a year, every other year, every third year) should be a requirement of any PI receiving R01 funding. I have never understood why there has not been a mandatory service requirement.

It is also worth mentioning that reviewers serving as standing members of RO1 study sections often receive seminar invitations by prospective applicants and are treated with expensive dinners/highest honorariums etc during their visits. This happens in my institution and everywhere else.

In my opinion I also think most full Profs are more supportive of new investigators than the junior faculty. I have done a lot of study sections over the years. Not to over generalize, but often it is more experienced reviewers who give PIs the benefit of a doubt when it comes to technical issues and who weigh significance and innovation more. I once heard a reviewer comment that the PI did not outline how they would genotype the mice, this despite numerous publications with said mice. In a 12 page application, you cannot get too bogged down by details.

The real problem is that most grants are not that distinguishable, probably 30-40% should be funded and cannot easily be ranked, yet SROs keep telling us to spread the scores. Rarely do I see one that is truly original and outstanding, because science is hard.

While we are on the topic of minimizing bias and maximizing fairness in the review process, this goal will remain elusive as long as anonymity only serves to protect the reviewer. This creates a conscious or unconscious bias, knowing that as a reviewer I can write whatever crosses my mind and will never be held accountable. anonymity should go both ways so reviewer doesn’t know whose grant s/he is reviewing, or the reviewer and applicant should be disclosed.

I have previously suggested what I am going to write here to Mike when we met in a conference in Portland in 2016. He said that he likes the idea.

Unfortunately, the NIH study sections’ members always have personal biases toward the PIs and their institutions. This is human nature and cannot be changed. To minimize that, the review should be anonymized in stages:

(1) the reviewer sees the Narrative and gives score. Once the score is entered the reviewer cannot change it anymore. Then she/he would see the other components of the grant, i.e., Specific Aim page, Research Strategy, etc. and enters her/his scores without the option to change. (2) At the last step, she/he will see who the PI is and their institution to give the PI-related score without the possibility of changing the other scores.

This way, the bias is minimized the scores will be more toward the project itself. Although not totally eliminated because the reviewer may guess who the PI is based on some minimal identifiers (e.g., research topic, it will be a more fair situation compared to now. I have received so many personal comments on my summary statements that I am getting used it these days.

I am just below the yellow line but I serve of a study section that is not directly related to my work, which often requires a lot of extra effort. I hope that by not being an insider, and having no competing interests, my presence on the panel accomplishes exactly what this new initiative would like to accomplish: more diversity. It is not always a good idea for me have an equal say on approach with colleagues who have decades of experience in the field. On occasion, however, an outsider’s view can counterbalance emphasis on the tried and true ways of evaluating an idea. I agree with the posts that warn against too many fresh reviewers, who are indeed keen to point out minor technical issues and fail to emphasize the significance and creativity of meritorious applications. Kenton Sanders also raised valid points with regard to the failures of the current system, and suggested solutions that might improve it.

I favor:

A. Obligate service by all grant-holders, in proportion to $$ value or number of grants held, tempered by:

i. Past review hx, which will be judged by the Chair and SRO both; perfunctory, vague, arbitrary, arrogant reviews exclude the right to participate in peer review in future. This will be part of the “investigator profile” for eligibility future reviews, and for repeat offenders in evaluating their own grant submissions.

ii. Stage of career; junior faculty need much more experience than one grant to appreciate the breadth, insights, frailties inherent in the grant writing and review process. I favor an even distribution emphasizing mid-level and senior people, with some junior faculty mentees who are placed under tutelage of a more senior member of the study section.

B. A larger number of reviewers per grant, say 4-5, rather than 2-3, particular for translational grants which obligate covering more ground, and therefore numerically more different realms of expertise. A breadth of expertise in review has advantages, but surely the informaticians will see different strengths from the molecular biologists from the clinicians. The most crucial aspects of the grants should have more than one opinion weighing in on them, perhaps judged in advance of reviewer assignment, by the Chair, who approximates a content expert.

C. The assignment of a Chair and Co-chair, to share these above assignment/analyses duties, and can be compensated for their extra work in some way, who combined can do some of the challenging and timeline-compressed assignment work above, in advance of actual review assignment.

D. Accountability of reviewers will be explicit. So those merely offering “sneer review” instead of peer review, provide only perfunctory and unsupported judgements on merit, incomplete reviews, opinion masquerading as biblical tenets, and poor defense at the reviewer meeting of their judgements, will be judged accordingly. Repeat offenders could have such marks weigh in on their own grant proposals in the future.

E. Consideration of anonymized applicants, like DoD, whereby the aims, concepts and strategies, are judged separately from the personnel performing them. This helps to even the playing field for junior level applicants.

F. Re-emphasizing innovation, nimbleness, modesty, and impact. The sequencing and big-data industries (in which I operate as well, hypocritically), for example, are overemphasized at great fiscal cost, to the detriment of the remaining myriad technologies that at smaller scale, can support smaller projects.

THe introduction of “bullet points” instead of reasoned text has contributed to errors and unhelpful reviews. The need to write a few logical sentences makes the reviewer formulate their criticism more carefully. The frequency of errors in reviews seems to have increased in the past 5 years. There should be a better way for applicants to respond to reviewer errors. Overall, “compared with every other method of review”, the Study Section review process has played an important part in the tremendous progress in biomedical research in recent decades. I think that one big motivator of accurate reviews is the desire to avoid public errors in the presence of peers at a live Study Section meeting. In my experience, the quality of discussion is higher much higher in “in vivo” Study Section meetings, compared with telephone meetings or written reviews. The need to defend your criticisms to other experts in a live meeting is a great motivator of accuracy. The cost of each review is a small fraction of the funds committed on the basis of the review.

Not everyone can be a good, fair, honest reviewer and NIH seems to keep dismissing that fact. Just because you have an NIH grant doesn’t mean you are capable of being a good reviewer. Some people are invited back again and again because they prove themselves capable, while others are removed from rosters because of completely legitimate reasons for concern. Developing a qualified pool of reviewers requires proactive training, mentoring and supervision. If it’s serious, cultivating a culture of quality review by letting its best train its newest should be what NIH focuses on instead of alienating its best reviewers while recruiting a pool of new, inexperienced people. Reviewing is a pain in the neck and done (well) for free by people who believe in service. What NIH truly needs is an overhaul of its whole process in the reality of inadequate funds. Having only three reviewers makes it all too easy for one person to swing the pendulum. The low paylines are disastrous and don’t mesh with the current review system. We’re missing out on the best science with pay lines hovering around 10%. There is no way any reviewer can do anything more than sort out the best, maybe 20%. Anything less than that is down to nit picking and personal opinion. The system is asking for more than it can reasonably deliver with its current financial situation.

It would be interesting to know how the number of reviews/person breaks down along the lines of gender and race.

Thank you for this important change in scientific merit review process. The VA has been also inviting reviewers based on scientific skills not necessarily based on one type of award funding R01 or its equivalent which we know is restrictive in many ways. May be NIH would follow similar process based on other factors ( career development awards etc) which will allow more diversity to the pool of reviewers.

As scientists, we often pride ourselves on our rationality and impartiality. As humans however we will often fail to achieve those lofty goals. The NIH policies try to reflect those goals as well, but by making them blanket policies, they ensure turnover, but sometimes they turn over some of the most meritorious of reviewers. The most astute chairperson I have served under was forced to relinquish that position and even his presence as a reviewer because he had served too long according to new NIH rules. This removed strength from the review process. I can understand it may also serve in general to remove individuals who have bad undue influence but a broad scythe cuts both. Similarly, the inability to sit on two panels during one round forces the SRO to find someone else to fill a spot. The NIH has program officers who select their reviewers on criteria of relevance and ability, i.e. merit, perspectives may differ there but one would assume folks at the NIH can distinguish a pompous ass from a hard working genius. Thus I think, instead of issuing blanket rules, particularly ones which change ever couple of years, the NIH would be better served with reviewable guidelines, ones which may not need to be followed to the letter and make the exceptions when they are appropriately justified. A last point, there may be a large pool of individuals who don’t serve, some of which certainly could and do a good job, however even among the currently reviewers there are some who shouldn’t. I have seen in committee as well as received reviews to grants which clearly indicated the particular reviewer either failed to read the grant or was out of their depth and in their ignorance decided to give a vague or nonsensical review. I would like to know about the process that goes into triaging those kinds of reviewers out the process all together and have them be under supervision when/if allowed back in.

agree, some reviewers “either failed to read the grants or were out of their depth and in their ignorance decided to give a vague or nonsensical review”. The irresponsibility could cause the applicant’s career. SROs need to make sure that the grants are assigned to the appropriate reviewers

I think this is a mistake. Full Professors are, in my experience, most supportive of young investigators.

Young investigators are not supported in general by young investigators. Perhaps this is my experience at MSFB but the idea that senior investigators are not supportive of young investigators is not reality.

1) More female reviewers should be recruited. The study sections are so male dominant and have been so for as long as the system has been implemented

2) it is true that the senior investigators appear to be more supportive to the young investigators, unfortunately, it does not seem so the other way around

3) SROs have to make every effort to assign the same reviewers to the resubmitted applications as this is the only chance for resubmission. It does not make any sense a resubmitted grant gets a worse score than the original submission. This happens often to many applicants

4) NIH must stress to the reviewers the use of language in their written reviews as well as in the live discussion at the study sections

this a great initiative and very important.

Reviewers of too many grants are as, if not more, suspect than those who do not review.

I would suggest a cap and a minimum.

The cap should be well below current top levels

Great Idea. It is also important to remove standing panel members who do not have R01s if the panel is reviewing R01s. Most of the times, the unfunded reviewers give hard time for grants than the funded reviewers without a clear rationale. This was a long overdue!!!

Reward those who do study sections with points that can be added to any grant submission in the future. We will be flooded with interested reviewers such that we can be picky about who serves. The primary reviewer of my last grant was almost certainly someone who only ever had a K award. Something must be done

Good moves–thanks!

All NIH awardees should be available to serve on at least 1 study section a year. Those with multiple grants and/or at the pinnacle of their careers must serve. It should be a mandated civic duty.

Broadening the pool of reviewers is an important goal. My concern has to do with the consequences of increasing the proportion of less experienced reviewers. I have chaired and served on study section for years, an experience that convinced me that crafting a fair, balanced and rationale review is a learned skill, that takes several rounds of review to master. I also find that many less-experienced reviewers tend to focus on relatively minor technical issues with an application, and that these issues disproportionately affect their scores. I hope CSR plans to proceed with caution in this initiative.

For the most part the SRO’s work hard to find qualified reviewers. However, sometimes they are forced to include less qualified reviewers since the experts recuse themselves for various reasons. What would help a study section most is having Chairs who are highly conscientious and demand fair and detailed reviews from the panel members. Having served as a Chair in 3 different study sections, I found that many reviewers give poor scores with no justification or high scores with marginal comments. This is a place where CSR can ensure that there is some quality in the reviews. Generic comments like “the proposal is too ambitious” without justification or “not enough details are provided” without highlighting what is missing are common problems. Also study section members should be mandated to submit their online reviews atleast a weak before so that the Chair and SRO can provide feedback to the reviewer to expand or clarify their comments.

Yes, good points. I think the move to bullet points for strength and weakness in the templates was a mistake and does not often convey the right message that a well written text can.

Noni – your efforts are certainly well-intentioned, but they will be ineffective for reasons that should be obvious given brief thought. Consider a stated goal: to bring varying scientific perspectives into the process. That effort will inevitably lead to a greater diversity of opinion on any given proposal, so that every proposal will have champions and critics. It is a naïve myth that expert reviewers can identify and agree on the “best” proposals. You are as aware as I am that no honest reviewer can truly and consistently distinguish among the top 20-30% of proposals.

I am between your yellow and red lines, and my experience suggests that the problem is not due to insufficiently “varying perspective” on the part of reviewers, but rather 4 ways that criticism is currently weighed in the review process:

First, almost any significant criticism by any of its 3 reviewers is enough to kill a grant, often throwing it into the triaged pile.

Second, criticism is given equal or even greater weight than praise, significance, cleverness, novelty, innovation, and potential for breakthrough.

Third, applicants are not allowed to answer criticisms; Reviewers frequently bring up entirely new criticisms on A1 applications, and applicants have no recourse but to submit a “new” proposal without any reference to prior criticisms that they regard as unfounded.

Fourth, reviewers are not held to account for their errors in criticism. When so many proposals are returned as “not discussed”, and so many written comments never brought up in discussion, reviewers are not even accountable to the rest of the committee, and not obliged to write things that are even objectively true. A reviewer who makes an erroneous statement should be just as exposed as an applicant who makes an erroneous statement in their application. This is an especially serious problem because so often applicants are more expert and better informed about the specific area of a proposal that the reviewer.

Let’s not be naïve about grant reviews – the wider the perspective you subject grants to during review, the more you will achieve regression to the mean, aka reversion to mediocre, safe, uncreative, less adventuresome science.

Bert, you make outstanding comments, and I want to second your points:

“Third, applicants are not allowed to answer criticisms; Fourth, reviewers are not held to account for their errors in criticism.”

Correct. I’ve seen this from the perspective of both reviewer and applicant, and it is a gravely serious issue. Of all the reforms that could be undertaken, this is probably the most crucial. If a review gets through the process with substantive errors, it should not be allowed to stand. As you point out, one erroneous negative review easily cancels out two factual glowing reviews.

Apart from the rare “rescue,” application, the process has no real checks and balances to handle an erroneous reviewer. In this case, the truth is no defense for anyone- not the other reviewers, not program officials, not CSR, and certainly not the applicant.

I admire CSR. They do a great job with very limited resources, and I like the continual re-invention to improve the process. One area long overdue for re-invention is the issue of you raise: errors.

Also, I would be very interested to see an analysis done on clearly erroneous reviews. Do they tend to come from “excessive” reviewers? Novice reviewers? Non-professors?

I strongly support this move to include qualified reviewers from more diverse backgrounds, and limit excessive review service from a group of reviewers.

I think that aiming for 50% full professors on the panel is not unreasonable standard because I think that the panel should reflect the composition of the community. If one looks at the make up of most departments, the percentage of full professors are high due to the relative clock for tenure and to full (6-12 years on average) vs total service years (~30 years). Of course, it is also a mistake to pack the committee full of full professors.

I’ve had funded R01 grants for more than 40 years. I think the study section system has outlived its usefulness and expends far more money than is necessary to bring people to meetings and pay lodging and food expenses. No one reads all of the grants at a study section meeting, yet everyone is required to vote on the quality of the grant. The vote is often based on a short and not very in depth analysis of the science, and there is a growing trend for reviewers to not even know much about the topic proposed or the techniques to be used in the project. The most persuasive or aggressive reviewer often has undue influence on the way in which the rest of the people vote (people that have not even read the grant!!). That is just a very poor way to obtain meritorious grant reviewing.

I suggest going to a system like that used for reviewing papers. I think every active R01 holder should be required to review a few grants per year. With over 22,000 people funded by R01s this would greatly expand the reviewer base. A computer should pick the list of reviewers with actual knowledge and experience in the topic and techniques of the proposed grant based on comparative searches of the submitted grant and all funded grants. A list of potential reviewers could be assembled in minutes and then reviewers could be recruited electronically. This could all be accomplished within hours of receipt of a grant, just like happens when scientific manuscripts are submitted. The grants should be reviewed online and reviews expected to be completed in less than 4 weeks. Reviewers should do this without knowing who else is reviewing the grant and sign confidentiality agreements with each review. More than 3 reviewers could be recruited to review each grant, providing a better statistical basis that would increase impact and quality of science. If each grant had 5-10 reviewers more credibility and depth of critique could be obtained. Scores outside 1 SD of the mean, high or low, could be discarded, and reviewers’ scoring trends could be followed quantitatively to be sure that bias is not being directed at certain topics, certain people, or certain groups of people.

I think non-competitive awards should be tied to reviewing. If one is asked to review grants during the year and turns them down, then their non-competitive renewal should be delayed. If one has a single R01 they may need to review less than 5 grants per year, but if one has multiple R01s, the number of reviewed grants should increase. A minimum number of grants should be required each year, if the investigator is asked, If my required minimum is 3 grants, and I am asked to review more, then those can be turned down. If my minimum is 3 and I am only asked to review 2 grants, then being under the minimum is not a problem. The minimum number of reviews will be more or less determined by the number of submission, but the required number of grants might be very few per year.

What are the advantages to such a system?

1. Far less expense for grant reviewing, fewer personnel at the Review Branch, less travel, less lodging and food expense

2. Far quicker than 6-9 month turn around on grants being reviewed; more efficient decisions for investigators

3. Saving time and energy for grant reviewers as they would not have to expend hours and hours traveling and sleeping in a poor quality hotel. West coast reviewers are at a much greater disadvantage than East Coast reviewers in the current system.

4. Reviewers could work in the comfort of their own offices with full access to the literature on the subject of the grant. This might increase the quality of the reviews.

5. Each reviewer might have far fewer grants per year, as the number of reviewers would be greatly expanded. This would reduce the burden of reviewing grants for the NIH and may increase quality.

6. Payment for grant reviewing ought to be like payment for reviewing papers – nothing. If you have grants, you are expected to contribute to the review of grants.

7. All of the saved resources could be used for funding MORE grants, a feature of this program that would be very popular with active investigators.

8. Having all R01 grant holders review grants would restore the notion of peer review and remove reviewers that may be inexperienced or in fact be quite bitter about not being able to obtain NIH funding,

9. Having more reviewers would dilute the negative efforts of scientists with bias toward the topic or investigator that submitted the grant.

10. Spreading the review process to such a wide group of reviewers would increase the scientific depth and quality of reviewing.

I would like to know if this idea is discussed and reviewed. I think adding efficiency to the grant review process is absolutely necessary to maintain the pace and quality of science funded by the NIH. The process currently is so inefficient as to be absurd.

I think the key to having unbiased and relevant

reviews of the NIH grant Submissions is to rotate

the committee members as Much as possible and feasible

I personally feel that there are plenty of willing

and eligible reviewers out there who would be

Happy to participate in this process even if never

Had NIH funding, but otherwise have a lot of

Clinical research experience, Such clinicians for

instance often Maybe excluded from this process

because of Limited or none prior NIH funding

This proposal quite appeals to me as an R01 funded investigator and as someone that has served as both a standing study section member and on ad hoc panels (and a west coast resident). One thing that I would add would be a collaborative phase after the initial review, similar to the eLife manuscript review model. This would be a discussion among the reviewers (which could be handled in an online chat) to resolve differences of opinion regarding strengths and/or shortcomings and to come up with a consensus final review and score.

Yes I think the reviewers pools need to expand. There several directions that affect health now day. NIH must include all possible directions to be more up to date in the new several directions evolving

The idea of appointing more early career investigators to study sections is misguided. The depth of knowledge directly correlates with seniority. In fact the idea may be counterproductive as very often early career investigators are more opinionated than established scientists and may be unsupportive to ideas that are contrary to their beliefs.

Great article and I support the recommendations.

As a reviewer who tries to serve on panels once or twice a year, I am taken aback at that anyone can serve nine times a year, year after year for twelve years. When do they do anything else? On my last panel I had to read over 1000 pages of applications, not counting all the extra material in the references section and more reading to fact-check claims. Perhaps they know their fields so well they can blast though the material without error.

I wonder if there has been any attempt to determine the kind of reviewers most likely to produce sloppy or inaccurate reviews. When factual errors crop up in reviews, are these more likely to come from these hyper-reviewers?

As long as I am on my “soapbox” let me address the issue of getting “new, young” reviewers on panels. We have routinely seen that new reviewers exhibit what was once termed “young NIH Reviewer Syndrome:, namely to try to show the panel how stringent they could be, and to focus almost exclusively on the approach. It was the “silverbacks” who tried to encourage them to be less focused on “approach”, and to consider other aspects of the application- significance, innovation, etc. Let’s please keep this in mind as you try to populate IRBs with untested reviewers.

The tone of this post is incredibly dismissive of the substantial efforts people that have been consistent reviewers have made to the review process while at the same time trying to encourage more enthusiastic reviewing–so basically the typical NIH incoherent, contradictory, doublespeak. Painting a picture of the most dedicated reviewers as a menacing group of people seeking “undue influence”, perhaps greedily seeking out “excessive ad hoc review service” for the dubious reward of continuous submission, is a complete slap in the face of reviewers who took their valuable time to volunteer their services for very little compensation, but as an act of service in direct response to a request from an SRO. This is the key point–the post alludes to, but really fails to take responsibility for the fact that the only way someone gets to be a reviewer is by the direct invitation of the SRO. These invitations are often written in desperate terms, and as someone who is above the red line, even when I have turned down review I often get a follow up email asking that I reconsider. I guess according to Ms. Byrnes I should apologize for this level of service. I certainly will make sure to do far less in the future. Perhaps one of the reasons SROs return to the same reviewers over and over is that many reviewers are terrible. CSR might make more of an effort to deal with these individuals, as they are very easy to spot and the entire committee, and more importantly the applicants, suffer in the face of poorly reasoned, poorly written, meandering reviews. Instead CSR has taken on the much more important task of demonizing the people trying to and often succeeding in doing a good job.

It is truly disappointing that 18% of active R01 holders have never served. I’ve never had an R01, and I’m definitely above the green line. Serving should be a requirement of funding.

Dear Dr. Byrnes:

Do you honestly think that those of us who volunteer our services repetitively, and to various IRBs do so only so that we can get a 2 wk extension on our own applications? That is an outrageously naive view. Many of us routinely accept the request for service because we have benefited over the years from NIH support. Most times that i get this “benefit”, I’m not even submitting an application! Many of us who have served multiple “sentences” on standing panel (Y3 in my case) view this as a duty associated with the continued support (since 1983) from NIH (pay back)!

On a recent review of an R01 renewal application by a standing SRG, I noticed many familiar names on the roster (5 of them in fact)…from when my K23 was reviewed by the same panel 10 years previously. I can appreciate SROs’ desire to keep previous charter members in their portfolio as “go-to” ad hoc reviewers in content areas that are not consistently well represented on the standing roster. But this practice likely contributes to the “gatekeeper” effect mentioned above and is not consistent with the spirit of broadening review perspectives. Once their service is complete, charter members should not be eligible to serve on the same study section in an ad hoc capacity.

Great move! It is also important to make sure a complete rotation of the key personnel (CSR organizer, chair, standing members, etc) on each study section every few years, to avoid bias and inappropriate influences.

This article implies that those reviewers who have done extraordinary service to the scientific community are somehow selfish and out to game the system. Cancelling the only benefit this level of service provides seems exactly backwards. What about the 18% of active awardees who have never reviewed in 12 years? Why is review service voluntary? If CSR is so concerned about broadening the pool, why not make an appropriate amount of review service mandatory for NIH awardees?

well, it has been a long time since I have been asked to review for NIH – and I worry that the system has become an echo chamber of conventional, rather truly innovative ideas.

I find this to be an excellent new approach to increasing the pool of reviewers. New blood is desperately needed as well as unbiased mentalities. I am a little concerned with the ability of junior faculty to provide adequate reviews due to inexperience. However, that will come with time.

Another avenue that might be explored is the use of emeritus faculty. There people generally have considerable experience, a wealth of knowledge and time available.

I note that your text fails to take into account the origin of the Review Process. Very senior, and well known, scientist committed to review the proposals of others. There is good reason for this. The individuals were not in danger of not having funding and worried about the need to support other promising scientist. I therefore am against the move to remove senior (let’s say, accomplished and recognized as such) investigators. I think it is appropriate to ask good reviewers for suggestions of younger possible members of panels. My experience with NIH review panels were less than wonderful. Members had long time experience and particular views — often inconsistent. I asked one person what he thought of a given grant – in his field. He said he did not read it! It was, in my opinion very good, at least. I also did not like the secret votes. A panel should reach consensus, but more importantly, say one thing and then vote another way. I served on an NSF panel, people felt free to discuss differences. Sometimes people changed and sometimes they did not, but at least there was an open discussion. I should say, most of the panel were extremely distinguished and famous. And I actually read all proposals.

I agree with the need to broaden reviewer diversity, while also maintaining the established investigator expertise and perspective. I am disappointed that many comments here are pointing towards the lack of experienced junior faculty and ad hocs as the issue in poor review quality. This is the point of the ECR program (which should be utilized on every panel IMO) – to train junior folks how to properly and fairly review grants, starting as Rev 3 and Discussants. You cannot learn how to do this until you do it. DoD gives example reviews and explicit rules on how to do so, why does NIH not do this for new (and all reviewers), and SROs should step in before panel with feedback to every reviewer if needed (like DoD does). Gatekeeping from established senior folks, giving benefit of the doubt to name recognition and the ‘they have a solid program’ or ‘they do good work’ vs the *actual* science that is on the page is a major problem. An active SRO will stop this type of discussion, but that might not change the scoring. The lack of ‘trust’ of innovative new methods and being up to date on new literature can be as much of a problem with established folks vs junior. This can also slow down or hurt high impact high innovation work vs incremental science. This is why maintaining expertise with diversity in mind, including balancing ECR and gender and race (to name a few) with established folks with the depth of view should be evaluated on each panel. This is especially important in the coming age of the limited renewals Sr folks are used to for fair play.

Hi there,

I am a full Professor and have an active R01 grant but never asked to serve as a reviewer for NIH grants. I regularly serve as a reviewer for DOD and VA grants. I will be happy to serve if I get a chance to review NIH grants.

Best,

Ming Pei MD, PhD

Professor of Orthopaedics

Director, Stem Cell and Tissue Engineering Lab

West Virginia University

What about having patient advocates as part of review process?

I think this would detract scientific rigor from the review panel. Patient advocates, although an important component for certain programs, may not have the breadth of knowledge or academic in-depth to fairly assess the merits of applications. Thus, I do not think the DoD patient advocate type of review panel is the most ideal use of patient advocate time.